Bias in Word Embeddings: What Causes It?

Word vectors are often criticized for capturing undesirable associations such as gender stereotypes. For example, according to the word embedding association test (WEAT), relative to art-related terms, science-related ones are significantly more associated with male attributes.

But what exactly is to blame? Biased training data, the embedding model itself, or just noise? Moreover, how effectively can we debias these embeddings? What theoretical guarantee is there that the subspace projection method for debiasing embeddings actually works?

In our ACL 2019 paper, “Understanding Undesirable Word Embedding Associations”, we answer some of these open questions. Specifically, we show that:

-

Debiasing word2vec1 and GloVe vectors using the subspace projection method (Bolukbasi et al., 2016) is, under certain conditions2, equivalent to training on an unbiased corpus.

-

WEAT, the most common association test for word embeddings, can be easily “hacked” to claim that there is bias (i.e., a statistically significant association in one direction).

-

The relational inner product association (RIPA) is a much more robust alternative to WEAT. Using RIPA, we find that - on average - word2vec does not make the vast majority of words any more gendered in the vector space than they are in the training corpus. However, for words that are gender-stereotyped (e.g., ‘nurse’) or gender-specific by definition (e.g., ‘queen’), word2vec actually amplifies the gender association in the corpus.

Provably Debiasing Embeddings

To debias word embeddings using the subspace projection method (Bolukbasi et al., 2016), we need to define a “bias subspace” in the embedding space and then subtract from each word vector its projection on this subspace. The inventors of this method created a bias subspace for gender by taking the first principal component of ten gender-defining relation vectors (e.g., $\vec{\textit{man}} - \vec{\textit{woman}}$).

To make any assertion about whether these debiased embeddings are actually unbiased, we need to define what unbiasedness is. We do so by noting that although GloVe and word2vec learn vectors iteratively in practice, they are implicitly factorizing a matrix containing a co-occurrence statistic3.

Let $M$ denote the symmetric word-context matrix for a given training corpus that is implicitly factorized by the embedding model. Let $S$ denote a set of word pairs.

- A word $w$ is unbiased with respect to $S$ iff $\forall\, (x,y) \in S, M_{w,x} = M_{w,y}$.

- $M$ is unbiased with respect to $S$ iff $\forall\, w \not \in S$, $w$ is unbiased. A word $w$ or matrix $M$ is biased wrt $S$ iff it is not unbiased wrt $S$.

For example, the entire corpus would be unbiased with respect to {(‘male’, ‘female’)} iff $M_{\textit{w}, \text{male}}$ and $M_{\textit{w}, \text{female}}$ were interchangeable for any word $w$. Since $M$ is a word-context matrix, unbiasedness effectively means that the elements for ($w$, ‘male’) and ($w$, ‘female’) in $M$ can be switched without any impact on the word embeddings. Using this definition of unbiasedness, we prove that:

For a set of word pairs $S$, let the bias subspace $B = \text{span}(\{ \vec{x} - \vec{y}\, |\, (x,y) \in S\})$. For every word $w \not \in S$, let the debiased word vector $\vec{w_d} \triangleq \vec{w} - \text{proj}_B \vec{w}$.

For any embedding model that implicitly factorizes $M$ into a word matrix $W$ and a context matrix $C$, the reconstructed word-context matrix $W_d C^T = M_d$ is unbiased with respect to $S$.

Lipstick on a Pig?

Although the subspace projection method is widely used for debiasing, Gonen and Goldberg (2019) observed that, in practice, gender can still be recovered from a “debiased” embedding space. How can we reconcile this empirical observation with our theoretical findings above?

-

In practice, the bias subspace $B$ is defined as the first principal component of $\{ \vec{x} - \vec{y}\ |\ (x,y) \in S\}$ instead of their span. Vectors can only be provably debiased when $B$ is the span.

-

The word pairs $S$ are not exhaustive; they rarely contain all the directions in embedding space that capture gender. For example, if

\[\vec{\textit{man}} - \vec{\textit{woman}} \not= \vec{\textit{policeman}} - \vec{\textit{policewoman}}\]and {(‘policeman’, ‘policewoman’)} $ \not\in S$, then the debiased word embeddings won’t be unbiased with respect to {(‘policeman’, ‘policewoman’)}. This would result in there being at least one direction in embedding space from which we could recover gender bias.

Though there are likely other factors at play, if only for these reasons, it is not surprising that what Gonen and Goldberg call the “lipstick-on-a-pig” problem persists in debiased embedding spaces.

Hacking WEAT

WEAT (Caliskan et al., 2016) is the most common test of bias in word embedding associations. In brief, it answers the following question: where relatedness is cosine similarity, are target words $T_1$ more related to attribute words $X$ than $Y$, relative to target words $T_2$?

For example, are science-related terms more associated with male attributes and art-related terms with female ones? According to the paper that proposed WEAT, yes, they are.

However, reasonable minds can disagree as to what exactly these ‘male’ and ‘female’ attribute words should be. While it’s easy to construct many different – but equally valid – sets for each attribute, the choice of words can lead to wildly different outcomes. We find that it is easy to contrive this selection to achieve a desired outcome, whether that is a statistically significant association in a given direction (i.e., bias) or no significant association at all (i.e., no bias).

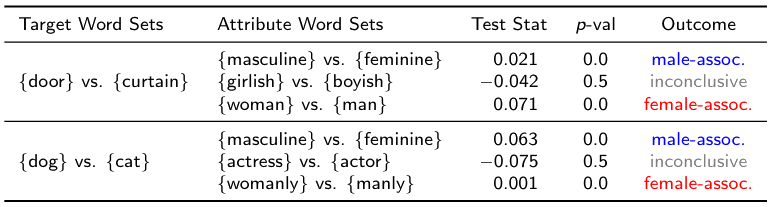

For example, is the word ‘door’ more male- than female-associated, relative to the word ‘curtain’? According to WEAT, it depends on the attribute sets.

We use single-word sets above for the sake of simplicity: similar (statistically significant) outcomes can also be obtained with larger target and attribute word sets.4 Note that the problem here is not that some of these outcomes are unintuitive, but rather that the outcome can be easily manipulated by the person applying the test.

RIPA

We suggest using a more robust alternative to WEAT:

The relational inner product association (RIPA) of a word $w$ with respect to a relation vector $\vec{b}$ is $\beta(\vec{w}; \vec{b}) = \langle \vec{w}, \vec{b} \rangle$, where

- $S$ is a non-empty set of ordered word pairs $(x,y)$ that define the association

- $\vec{b}$ is the first principal component of $\{ \vec{x} - \vec{y}\ |\ (x,y) \in S\}$

For example, if you wanted to calculate the genderedness of the word ‘door’, you would:

- Take the first principal component of $\vec{\textit{man}} - \vec{\textit{woman}}$, $\vec{\textit{king}} - \vec{\textit{queen}}$, etc. Call this $\vec{b}$.

- Calculate the dot product of $\vec{b}$ and $\vec{\textit{door}}$.

RIPA generalizes Bolukbasi et al.’s (2016) idea of measuring bias by projecting onto $\vec{\textit{he}} - \vec{\textit{she}}$ by replacing the difference vector with a relation vector $\vec{b}$. Using a relation vector – as opposed to, say, a higher-dimensional subspace – makes RIPA interpretable: in the example above, positive RIPA values indicate male association and negative RIPA values indicate female association.

Why use RIPA?

RIPA is derived from the subspace projection method and is easy to calculate. Other than its simplicity, it has three advantages:

-

It is more robust to the choice of word pairs that define the association than WEAT is to its attribute word sets. Using (‘male’, ‘female’) instead of (‘man’, ‘woman’) to define the gender relation vector, for example, would have a negligible impact on $\vec{b}$. While RIPA is not completely immune to such changes, because of how $\vec{b}$ is defined, it is more robust than WEAT.

-

If only a single word pair $(x,y)$ defines the association, then the relation vector $\vec{b} = (\vec{x} - \vec{y}) / | \vec{x} - \vec{y} |$, making RIPA highly interpretable. For example, for word2vec, RIPA has the following statistical interpretation:

\[\beta_{\text{W2V}}(\vec{w}; \vec{b}) = \frac{1/\sqrt{\lambda}}{\sqrt{-\text{csPMI}(x,y) + \alpha}} \log \frac{p(w|x)} {p(w|y)}\]where csPMI refers to the co-occurrence shifted PMI5, and $\lambda \approx 1, \alpha \approx -1$ in practice.

-

An obstacle to using any debiasing method is identifying which words we want to debias; we should debias ‘doctor’ but not ‘king’, for example, because the latter is gender-specific by definition. We propose a simple heuristic: debias a word $w$ iff

\[| \beta(\vec{w}; \vec{b_{\text{actual}}}) | < | \beta(\vec{w}; \vec{b_{\text{stereo}}}) |\]where $\vec{b_{\text{actual}}}$ is created using gender-defining pairs such as (‘man’, ‘woman’) and $\vec{b_{\text{stereo}}}$ is created using gender-stereotypical pairs such as (‘doctor’, ‘midwife’).

Compared to Bolukbasi et al.’s (2016) supervised approach for finding which words to debias, our simple heuristic works much better.6 Note that we don’t change the debiasing method at all – we only change the selection of which words to debias.

Breaking Down Bias

Because RIPA has such a clear statistical interpretation for word2vec, we can compare the genderedness in embedding space with the genderedness in the corpus to figure out $\Delta_g$, the change induced by the embedding model. For example, if the relation vector $\vec{b}$ were defined only by the pair (‘man’, ‘woman’), then

-

the genderedness of word $w$ in the word2vec space would be

\[g(w; \textit{'man'}, \textit{'woman'}) = \frac{\langle \vec{w}, \vec{\textit{man}} - \vec{\textit{woman}} \rangle}{\|\ \vec{\textit{man}} - \vec{\textit{woman}}\ \| }\] -

the genderedness of word $w$ in the corpus (a.k.a., RIPA in a noiseless word2vec space) would be:

\[\hat{g}(w; \textit{'man'}, \textit{'woman'}) = \frac{1/\sqrt{\lambda}}{\sqrt{-\text{csPMI}(\textit{'man'}, \textit{'woman'}) + \alpha}} \log \frac{p(w|\textit{'man'})} {p(w|\textit{'woman'})}\]

We measure $\Delta_g$ as the change in absolute genderedness because some words may be more gendered in the embedding space than in the corpus, but in the opposite direction. In the paper, we estimate $\Delta_g$ with not just (‘man’, ‘woman’), but several other gender-defining word pairs.

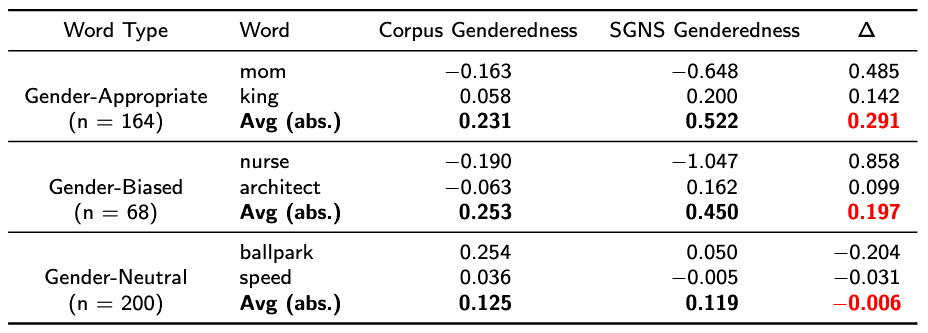

As shown in red in the last row, gender-neutral7 words, which comprise the vast majority of words in the vocabulary, are on average no more gendered in the embedding space than in the corpus. However, due to noise, individual words may be slightly more or less gendered in vector space.

In contrast, words that are gender-stereotyped or gender-specific by definition are on average significantly more gendered in embedding space than in the training corpus. In the paper, we explore some theories for why this is the case.

Conclusion

Only words that are gender-specific (e.g, ‘queen’) or gender-stereotyped (e.g., ‘nurse’) are on average more gendered in embedding space than in the training corpus; the vast majority of words are not systematically more gendered. When measuring bias in word embedding associations, we recommend using RIPA instead of WEAT, as the latter’s outcomes can be easily contrived.

Once bias is identified, debiasing via subspace projection can, under certain conditions, be provably effective. However, these conditions are difficult to satisfy in practice, leading to some bias persisting in “debiased” embedding spaces. As NLP moves away from static embeddings to transfer learning (e.g., BERT), leaving out training data responsible for undesirable associations (see Brunet et al., 2018) will likely be more tractable than explicitly debiasing representations.

If you found this post useful, you can cite our paper as follows:

@inproceedings{ethayarajh-etal-2019-understanding,

title = "Understanding Undesirable Word Embedding Associations",

author = "Ethayarajh, Kawin and Duvenaud, David and Hirst, Graeme",

booktitle = "Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics",

month = jul, year = "2019", address = "Florence, Italy",

publisher = "Association for Computational Linguistics",

url = "https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P19-1166",

doi = "10.18653/v1/P19-1166",

pages = "1696--1705",

}

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Krishnapriya Vishnubhotla, Jieyu Zhao, and Hila Gonen for their feedback on this blog post! This paper was co-authored with David Duvenaud and Graeme Hirst while I was at the University of Toronto.

Footnotes

-

By word2vec, we exclusively mean skipgram with negative sampling (SGNS). We do not discuss CBOW. ↩

-

These conditions are difficult to satisfy in practice, however, which allows some bias to persist in the debiased embedding space. This may partially explain the lipstick-on-a-pig problem (Gonen and Goldberg, 2019). ↩

-

For details about the implicit factorization done by skipgram with negative sampling, refer to Levy and Goldberg (2014). ↩

-

For example, {‘door’, ‘cat’, ‘shrub’} is significantly more female-associated than {‘curtain’, ‘dog’, ‘tree’} when the attribute words are {‘woman’, ‘womanly’, ‘female’} and {‘man’, ‘manly’, ‘male’} ($p < 0.001$). Larger word sets are associated with smaller effect sizes but still yield highly statistically significant WEAT outcomes. ↩

-

In brief, $\text{csPMI}(x,y) = \text{PMI}(x,y) + \log p(x,y)$. See my previous blog post for a more detailed discussion of the co-occurrence shifted PMI. ↩

-

For a fair comparison with the supervised approach, we use the methodology in Bolukbasi et al. (2016) regarding gendered word analogies for evaluating the usefulness of the RIPA-based heuristic. However, the focus of our paper is on bias in word embedding associations, not word analogies. ↩

-

We identified gender-appropriate (e.g., ‘king’) and gender-biased (e.g, ‘nurse’) words by plucking them from the gender-appropriate and gender-biased word analogies in Bolukbasi et al. (2016), which were constructed with the help of crowdworkers. We considered all words that did not fall into these categories to be gender-neutral: neither gender-specific by definition nor associated with any gender stereotypes. See the paper for details. ↩