The most hated part of Claude Code is compaction. But why?

Picture this—you’re deep into a Claude Code session, burning thousands of tokens, blithe to the finiteness of your context window. Then comes the dreaded “Context left until auto-compact: 10% … 5% … 0%”. The prescient among us (not me!) proactively call $\texttt{/compact}$ before the counter hits zero; the rest of us let auto-compaction take the wheel, holding our breath for the few moments before Claude emerges anew, ready to continue. Compaction is the process by which the context window is freed by discarding or summarizing parts of the context while (in theory) not changing model behavior.

But the new Claude is not the old Claude.

The agent that emerges after compaction is haunted by context ghosts: phantom remnants of prior context that are enough to influence model behavior but not enough for the agent to act according to the user’s expectations. These ghosts:

- Make unverified assumptions about what was previously done.

- Deviate in subtle ways from plans that were laid before.

- Try things that have already been tried, wasting tokens.

Why does this happen? Compaction induces distribution shifts, both literal and perceived. It’s a little known fact that standard post-training with PPO/GRPO implicitly samples from a biased probability distribution that reflects human perception (see: the humanline paper); this not only increases user utility but also makes post-training more efficient. However, at inference-time, compaction changes the latent state the agent is in without accounting for user perception, creating context ghosts.

It is often difficult to articulate precisely what is wrong with the agent. In other cases, it is clear: for example, a Reddit user reports that after compaction, the model steamrolls any request to do planning and just goes straight to coding. Context ghosts are different from context amnesia, which is used to refer to the stateless nature of agents across conversations and forgetfulness within a conversation (due to context rot, compaction, or some other reason). Context amnesia can be a feature of context ghosts, but the latter describes a broader set of deviant behavior that is ultimately defined in relation to the observer, the user.

Whether we want to exorcise context ghosts or just avoid them to begin with, we not only need to consider the first-order model shift, but the second-order shift in human perception.

Post-Training Bakes in Human Perception

When I say human perception, I’m specifically talking about prospect theory, which was developed by Kahneman and Tversky (you might know the former from ‘system 1 vs system 2 thinking’) to explain how humans perceive random variables.

Prospect theory starts from a simple observation: humans don’t act like expected-value maximizers. Take a gamble in which you win 100 dollars with 80% probability and lose 100 dollars with 20% probability—how much money would you need to be offered to not play? Classical decision theory says a rational agent should accept the expected value: $0.8\cdot 100 + 0.2\cdot (-100) = +60$. But most of us would accept far less than $60 to forgo the gamble.

This is because losing $100 feels a lot worse than gaining the same, the 20% chance of losing feels bigger than it actually is, and so on. Collectively, these insights into how humans actually make monetary decisions were formalized into prospect theory, for which Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in economics (Tversky had passed away by that point).

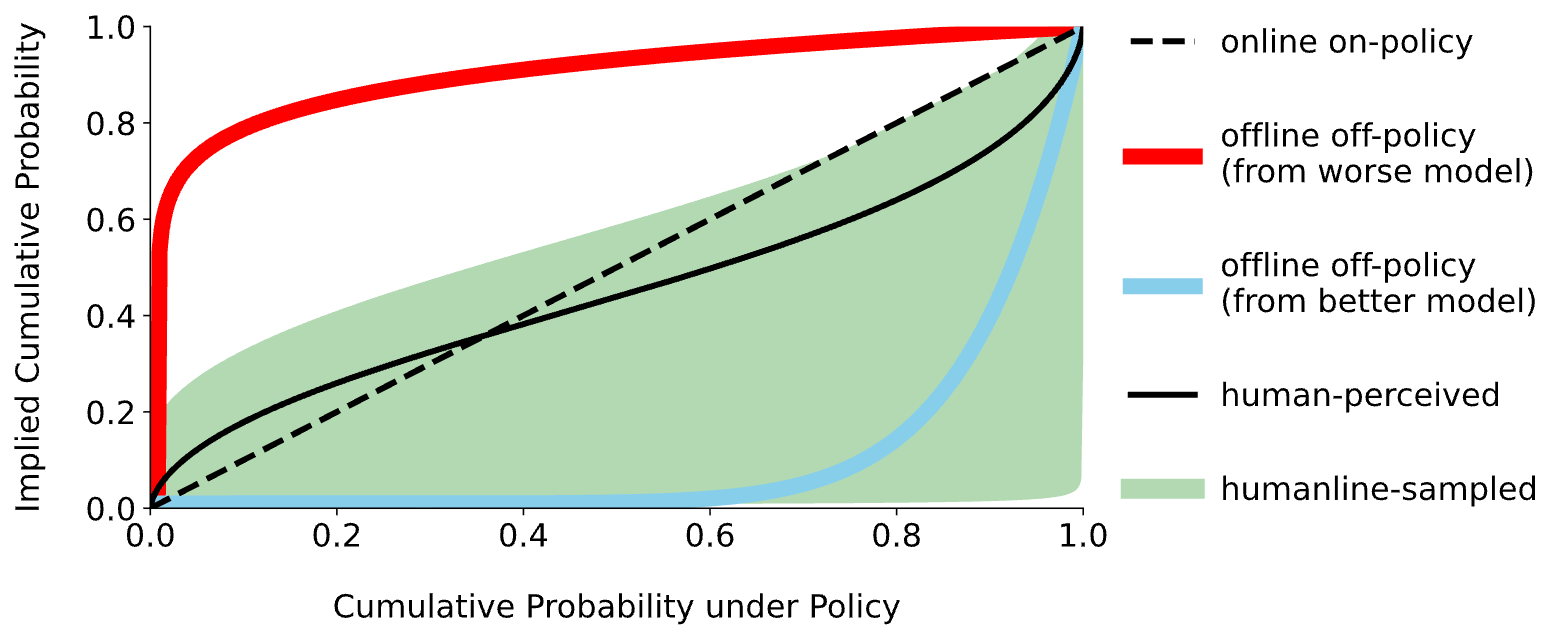

What’s fascinating is that prospect theory has crept into post-training without us even realizing it. If, instead of using monetary rewards measured in dollars, we switched to implied rewards (i.e., surprisal in the post-training sense) measured in bits of information, we can frame the goal of post-training as follows: increase the implied rewards of “good” outputs and decrease the implied rewards of “bad” ones. The specific objective we use shapes the utility and probability of these implied rewards. DPO, PPO, and GRPO, it turns out, carve out a utility function that is very similar to the typical human’s utility function in prospect theory.

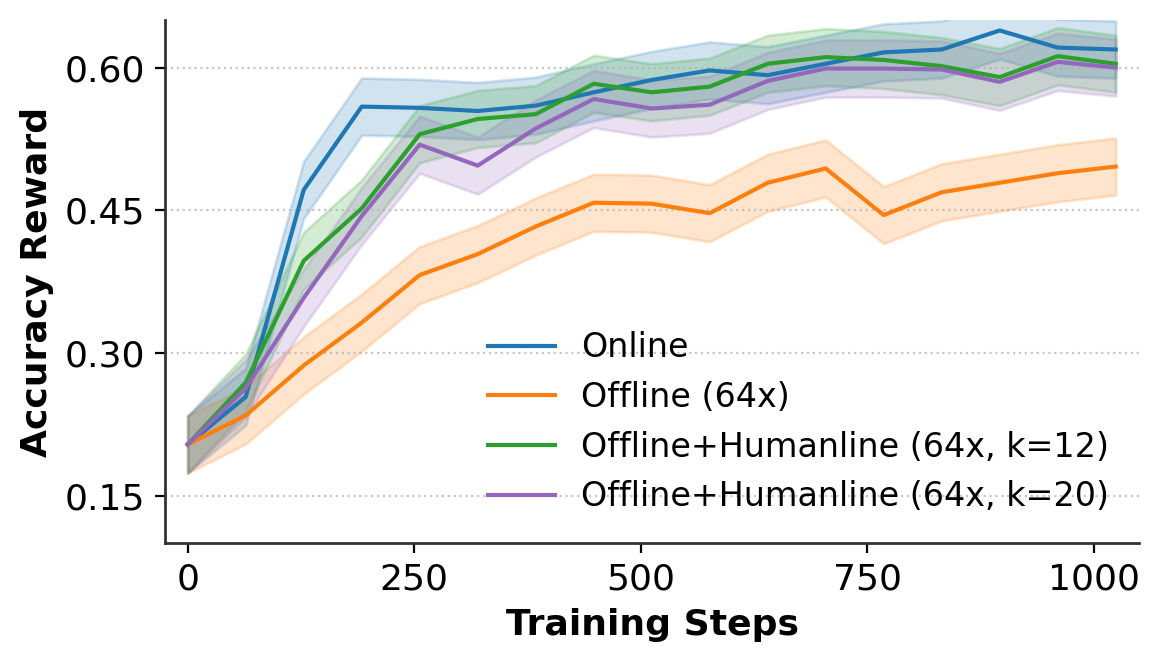

But human perception also biases how we see probability: we overestimate the chance of near-impossible events (getting hit by lightning) and near-certain ones (getting to work) at the expense of everything else. It turns out that when we sample from the model we’re post-training and then clip the implied rewards, as done in PPO and GRPO, we effectively change their distribution in a way that reflects the human-biased perception—this is called humanline sampling.

This might sound like a bad thing (shouldn’t probabilities be objective?), but not only does this help maximize human utility—which matters if humans are going to be the end users, like with coding agents—it makes post-training much more efficient. In fact, if we incorporate the human-biased perception of probability more thoroughly into GRPO, creating humanline GRPO, then we can sample data up to 20x less frequently without any performance degradation.

Compaction Ignores Human Perception

Why do things go wrong when we compact our agent $\pi_\theta$? During compaction, the first-order goal is:

\[\pi_\theta(y\mid x,\texttt{summary}) \approx \pi_\theta(y\mid x,\texttt{history}) \quad \forall\ x\]But even if you could achieve this (you generally can’t, because a summary is inherently lossy), it still wouldn’t ensure the user experiences continuity. If $F(\cdot\mid x, \texttt{summary}; \theta)$ is the cumulative distribution over implied rewards induced by the model and $H(\cdot)$ is the nonlinear transformation of that under human perception, then the condition we actually want to satisfy is:

\[H(F(\cdot \mid x,\texttt{summary}; \theta)) \approx H(F(\cdot \mid x,\texttt{history}; \theta))\]If the compacted summary loses a minor edge-case constraint, the literal probability shift is small, but the human user, who expects strict adherence to the conversation history, could perceive this as a massive failure. Compaction today tends to meet neither condition: it doesn’t reliably preserve the literal distribution over outputs, and it definitely doesn’t preserve the human-perceived distribution over implied rewards.

Sub-Agents and RLMs

Sub-agents and Recursive Language Models (RLMs) are a practical way to avoid context ghosts—not by fixing compaction, but by making compaction less necessary.

The basic idea is architectural: you offload bounded chunks of work to other models. For example, given some code completion task, the parent might write a high-level plan and delegate tasks such as “try three approaches and report back”. The result of these sub-tasks, or a summary of the new state of the world, make their way back to the parent. This does two things:

- It preserves headroom in the parent context window. The parent can keep more of the true conversation history around, so you hit the compaction threshold later (or not at all).

- It keeps the parent policy closer to human expectations. Because the parent isn’t constantly rewriting itself around an ever-growing scratchpad, it’s less likely to drift into the weird “half-remembered, half-invented” state that shows up right after compaction.

But if the parent crosses the context limit, compaction still happens and the same perceptual mismatch problem returns. Moreover, sub-agents return partial views by design, meaning that we’re still living inside a hierarchy of compactions.

At the end of the day, neither sub-agents nor RLMs make compaction perceptually aligned (nor is it their goal to do so!). But in reducing the demand for compaction, they still markedly improve the user experience.

Open Problems

There are three ways to deal with context ghosts:

- (old) Try to avoid them by scoping out modular tasks that fit within the span of a single conversation, or by offloading as much of the computation as possible to other models, à la sub-agents and RLMs.

- (old) Give the compacted model more context, steering it towards the desired behavior, at the cost of your own time and more tokens. This is what I end up doing most of the time, even though I recognize it as sub-optimal (in my defense, I suspect that I am not alone in doing so).

- (new!) Make the compacted model better fit the human perception of how it should behave, either by changing the model’s behavior through the compacted summary or by changing what the user expects of the compacted model. The second-order change is what is most interesting. It is tautological that any summary will be lossy, but the lossiness need not create context ghosts. If the agent is transparent and explicit about what is distilled and what is not, its limitations go from eerie to mundane. But what is the best way to do this—a diff of what was retained vs. dropped? A confidence flag? An agent that more proactively asks questions?

In an ideal world, interacting with a coding agent would be a truly seamless experience, with context windows that feel infinite even when they aren’t. Getting there requires not only thinking about the agent, but about the human on the other side too.